Empowerment Starts Here

This site is dedicated to the professional and academic work of Dr. Angela Dye.

When Delegation Becomes a Question of Permission

This is Week 6 in a 12 Week Series on Systems-based Leadership.

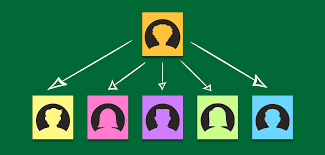

In executive leadership, delegation is often described as a matter of efficiency—an adjustment of workload meant to preserve time, prevent burnout, or improve productivity. But in practice, delegation reveals something far less technical and far more structural. It exposes an unspoken question embedded inside many organizations:

Who is allowed to hold authority without performing visible labor to justify it?

The moment power begins to circulate—moving from a single central figure into roles, systems, and shared capacity—organizations do not respond neutrally. They respond emotionally. What appears, on the surface, to be feedback about effort or competence is often something else entirely: a reaction to authority detaching from constant performance.

I began to recognize this pattern not during moments of failure, but during periods of stabilization—when systems were strengthening, capacity was expanding, and the work no longer depended on my physical presence to continue. It was in those moments that certain phrases surfaced with striking consistency. Delegation was described as laziness. Structural leadership was framed as incompetence. Authority itself was quietly questioned.

Over time, the pattern clarified.

These were not operational critiques.

They were signals of resistance to redistributed power.

Delegation, I realized, is rarely interpreted as a managerial choice.

It is experienced as a political shift.

And once that becomes visible, the conversation changes. Delegation is no longer primarily about efficiency or workload. It becomes a diagnostic—revealing whether a system is capable of allowing power to circulate beyond the person who first held it.

Why Organizations Misunderstand Delegation

Most leadership frameworks describe delegation as a technical skill. Leaders are encouraged to distribute tasks in order to increase efficiency, prevent burnout, and improve organizational output. Within this logic, delegation appears neutral—simply a smarter way to manage time and talent.

Yet real organizations rarely experience delegation as neutral. They experience it as redistribution. When authority moves away from a single visible figure and begins to circulate through roles, teams, and structures, the emotional response is rarely about workflow. It is about legitimacy. Questions emerge—sometimes spoken, often silent—about who now holds influence, whose voice carries weight, and whether authority has been earned in the “proper” way.

This reveals a deeper structural truth:

delegation exposes the hidden rules governing who is allowed to lead.

In systems where legitimacy is tied to visible exhaustion, a leader who is no longer performing constant labor can appear suspect. In hierarchies stabilized by control, distributed authority can feel dangerous. What presents itself as resistance to delegation is often resistance to a shift in power that the system was never designed to absorb.

Resistance as Structural Preservation

It is tempting to interpret resistance to delegation as interpersonal conflict or cultural misunderstanding. Doing so keeps the analysis safely within the realm of personality. But sustained patterns across organizations suggest something more durable at work.

Systems are designed to preserve themselves. They stabilize around familiar distributions of authority, recognizable performances of leadership, and historically validated pathways to legitimacy. Delegation disrupts each of these simultaneously. It separates authority from constant visibility. It allows competence to exist outside traditional hierarchies. It introduces the possibility that leadership is architectural rather than performative.

From the system’s perspective, this is destabilizing.

If authority can circulate, then control is no longer guaranteed.

If capacity can expand, then hierarchy is no longer fixed.

What appears to be skepticism toward a delegating leader is often the system’s attempt to restore equilibrium. The critique is not truly about the leader’s behavior. It is about the threat posed by distributed power.

Understanding this distinction is essential for executive maturity. Without it, leaders internalize structural resistance as personal failure and retreat back into overwork—re-stabilizing the very bottleneck that limits organizational growth.

From Labor to Architecture

Early leadership often equates credibility with effort. Doing everything signals commitment. Holding every decision demonstrates responsibility. Remaining constantly present reassures stakeholders that the work is protected. These instincts are understandable, particularly in fragile or emerging organizations.

But credibility built on constant labor is structurally unsustainable. When a system requires the leader’s uninterrupted presence to function, the organization has not matured. It has merely centralized dependency. Exhaustion becomes inevitable, not because the mission is too large, but because the design is too small.

Executive leadership requires a different orientation. The task is no longer to perform the work, but to ensure the work can occur without you. This shift—from embodiment to architecture—marks the transition from founder energy to systemic leadership. Delegation becomes the primary mechanism through which capacity multiplies, information flows, and resilience forms.

If the system cannot produce in your absence,

you are not leading it.

You are holding it together.

True authority at the executive level is measured not by how much you do, but by how much the system can do because of what you designed.

V. Translation to the Executive Reader

Many leaders encounter this paradox in isolation. They delegate responsibly, build capacity intentionally, and design structures meant to outlast their own labor—only to face criticism that feels personal rather than structural. The temptation is to return to visibility, to reclaim control through overwork, and to prove worth through exhaustion.

But the deeper question is not why delegation feels misunderstood.

The deeper question is:

What distribution of power is your delegation disrupting?

When delegation is resisted, it often signals that real transformation is underway. Power is beginning to circulate. Authority is detaching from performance. Capacity is expanding beyond a single individual. These are not signs of failure. They are indicators of structural change.

And structural change is the only pathway to sustained production, prosperity, and growth inside complex human systems.

Power that cannot circulate cannot multiply.

And power that cannot multiply cannot transform the conditions it was meant to change.

Delegation, then, is not a managerial technique.

It is one of the clearest diagnostics of whether a system is capable of becoming more than the person who founded it.